Student succesvol als Kennismigrant

The data collected from 2006 until 2009 show that the financialcrisis dealt a serious blow to international labor migration,decreasing it by 7%. Free-circulations movements within theEuropean Union Schengen area declined even more drastically by 36%,comparing numbers from 2009 and 2007. This has primarily to do withthe economic slump.

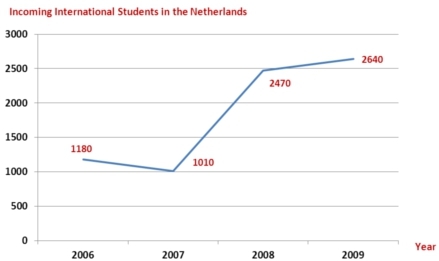

Overall, international student flows to OECD members grew in themajority of countries. Between 2007 and 2008, this number rose by5% which is a notch higher than the average 3% increase between2004 and 2008.

The Netherlands are an exception to this phenomenon. The numberof international (non-European) students remained stuck at 10.000while influx growth slowed from 18% to 9%. If you put the share ofinternational students in relation to population size, the Dutchscore even lower on internationality, well behind countries likeGermany, Czech Republic and Greece.

The number one source of foreign students in OECD countries isChina (410.000, or 18%), followed by India (163.000, or 7%) andSouth Korea (110.000, or 5%). Authors of the

17-33% of international graduates stay

Data show that between 17% and 33% of foreign students stay intheir host country upon graduation. This insight is especiallyimportant for the ever-ageing countries in the European Union whoare in desperate need for highly qualified workers bolstering theireconomies.

In this area, the Netherlands does quite well. 27% of allinternational graduates extend their stay to find a job at Dutchbusinesses. Other countries such as Austria perform much worse witha “stay rate” of merely 17%. France and Canada lead the pack with32% and 33%, respectively.

The British, meanwhile, experienced the largest increase ofmigrants changing their status to permanent residence (14%).According to the OECD analysts, this primarily has to do withstudents deciding to stay in the UK after graduation andconsequently does not indicate a sudden influx of immigrants.

Main obstacle for foreign graduates looking for a job remainsthe language barrier. Especially countries like the Netherlands,Germany and Austria who offer tertiary education in English need tolook for ways to educate international graduates to speak thedomestic language.

In France and Spain, this is not an issue since most studyprograms are in French and Spanish. This suggests that impactfulinternationalization of the Netherlands’ higher education sectorthen goes hand in hand with integrating Dutch language courses withstudy curricula.

Source: OECD Migration Report 2011

Liberate or Restrict?

The OECD report further outlines the different policies itsmembers adopted towards migration. Finland took a more liberalapproach by introducing changes to its Nationality Act effectivefrom September 2011.

International students will then be eligible to gain Finnishcitizenship within 5 years of staying in Finland.Half of the timethey spent studying there will count for this rule as well.Similarly, other countries like Norway, Switzerland and Japan bynow grant foreigners at least 6 months to look for a job after theygraduate in their host country.

Great Britain, by contrast, is depicted as implementing mostrestrictive measures. This insight is not surprising. Seeing massesof immigrants arrive at London Heathrow is definitely a horrorvision to David Cameron and in particular his supporters.

Only last year, Prime Minister Cameron introduced a

Other English speaking countries follow suit. In Australia, thistakes the form of increasing compliance controls fighting spreadingdocument fraud of visa applicants. Even Canada tightened theissuing of work permits. Previously, it was sufficient to havestudied one year at a Canadian university. Now, one’sspecialization is required to be on a skills shortage list unlessyou already have a final employment offer.

Meest Gelezen

Vrouwen houden universiteit draaiende, maar krijgen daarvoor geen waardering

Wederom intimidatie van journalisten door universiteit, nu in Delft

Hbo-docent wil wel rolmodel zijn, maar niet eigen moreel kompas opdringen

‘Burgerschapsonderwijs moet ook verplicht worden in hbo en wo’

Raad van State: laat taaltoets nog niet gelden voor hbo-opleidingen