Mediocrity in European HE

Europe has much less people enrolled in higher education that most Europeans think. The US, Canada, Japan South-Korea and Australia all outperform Europe, and this “can hinder competitiveness and undermine Europe’s potential to generate smart growth”. This is the conclusion of the European Commission in their assessment of the Horizon2020 targets for tertiary education.

Italy versus Ireland

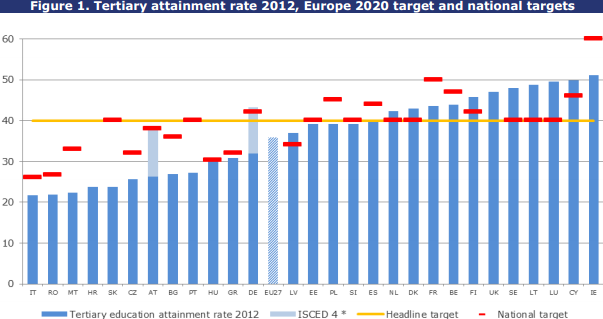

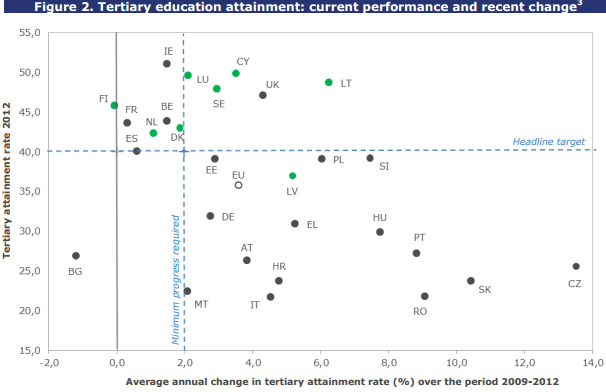

The European wants that at least 40 percent of the 30-34 year olds have a higher education degree in 2020. Twelve EU countries reached the European target, but overall 35.5 percent of the European youth has a higher education qualification. If the national targets are met in 2020, the attainment level will stick at 38 percent.

“While European labor market projections indicate that around 35 percent of all jobs will require tertiary graduate-level qualifications by 2020, only 26 percent of the EU’s labor force was qualified at this level in 2010.” However, the European Commission states that “current trends in tertiary education participation suggest that the headline target of 40% is likely to be met”.

Italy has become the schlemiel of Europe. The country with the oldest university has the lowest enrollment rate (21.7 percent) of Europe, but the least ambitious target as well (26%). Romania, Hungary and Greece don’t do much better. On the other end of the spectrum Ireland can be found. It is the only country with more than 50 percent of its youth enrolled in higher education (51.1%) and has set the ambitious target of 60 percent.

Include students from all walks of life

The European Commission concludes that there are three main challenges for Europe to remain competitive in the globalized economy and to stimulate “smart growth”. First, the access to higher education has to be broadened to “include students from all parts of society”. Students from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds or geographical locations, as well as students from ethnic minorities or with disabilities need to be given special attention.

“While important from a social equity perspective, broadening access for under-represented groups is crucial for countries that are still making the transition from elite to mass higher education systems and for countries facing demographic decline.” Although relevant for most Member States, this message is especially directed at Bulgaria, Romania, the Czech Republic, Greece and Hungary.

Added value of higher education

The second recommendation is to reduce drop-out rates the time it takes to complete a degree. “Lengthy study periods (Denmark) and a high proportion of students who fail to graduate undermine the efficiency of higher education systems. To increase the efficiency of public investment in higher education, Austria, Belgium, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland Romania, Sweden and Slovenia need to make particular efforts to reduce high drop-out rates.”

Finally, improving the quality of higher education and making it more relevant. The added value of a higher education degree will be key to increase the enrollment rates throughout Europe. However, at the moment there is no good way to assess the quality and relevance of higher education.

“In the absence of such data, graduate employment rates are one criterion for assessing the relevance of higher education provision to the needs of the labor market, although these employment rates are also affected by short-term fluctuations in labor demand due to economic cycles.” When these criteria are used, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal stand out as Member States where recent higher education graduates have greatest difficulties in finding work. Whether these numbers at this moment say something about the education system of these countries is not very likely.

Flexibility without financial barriers

The European Commission proposes several measures to raise the attainment levels the coming years. The most important is removing financial barriers to higher education, “an area where current policy trends vary”. Another important recommendation is to “bring more flexibility into the routes by which people enter higher education”.

“It is important to ensure effective transition pathways from vocational education and training to higher education as a means to overcome barriers to broadening access to higher education. Improving the recognition of knowledge already acquired in non-formal contexts is an important measure for many Member States, particularly in order to encourage more adult learners to enter higher education.”

Countries that have “relatively open access to higher education” should improve their guidance and counseling. That way, students will choose more appropriate courses and will be better supported. The commission urges for “more student centered approaches to learning, with manageable staff-student ratios and intelligent use of ICT-support”. The development of interdisciplinary learning paths can improve the employability of graduates.

German-speaking women

Gender differences are large in higher education. With an attainment rate of 39.6 percent, women almost close their 40 percent target. The attainment rate of men on the other hand is only 31.6 percent. In most countries girls vastly outnumber boys on universities. In Latvia even 85 percent more women study than men.

In Germany, Austria and Luxembourg the gender gap is much smaller. This is a remnant for the once big attainment gap in the favor of men. When compared to the Baltic, the Balkan and Scandinavia it becomes clear that Germany made some large steps, but it is still possible to let the number of women at universities grow.

Meest Gelezen

‘Free riding brengt het hoger onderwijs in de problemen’

Vrouwen houden universiteit draaiende, maar krijgen daarvoor geen waardering

Hbo-docent wil wel rolmodel zijn, maar niet eigen moreel kompas opdringen

‘Sluijsmans et al. slaan de plank volledig mis’

Aangepast wetsvoorstel internationalisering dient vooral samenleving in plaats van student